Editor’s Note: While many Chinese Christians have written throughout the history of the house church, publication of original Christian works in Mandarin lags behind the demand for theological and devotional resources. As a result, Chinese house churches have frequently looked to the West for texts to translate, and are often particularly attracted to older, historic works.

One Chinese pastor has recently undertaken to translate The Valley of Vision, a collection of Puritan prayers, into Mandarin. We recently spoke with him about this project.

This interview has been edited for both length and clarity.

China Partnership: How did you first become familiar with Valley of Vision?

Another Chinese pastor gave me a copy of Valley of Vision as a gift when I visited him at his seminary in the States. He is back in our city in China now, and we pastor at the same church. He told me that this is a very profound and influential work which is good for personal devotion. Because of this, I began to read it.

Never miss a story

CP: How did the book impact you? Do you think it will resonate with other Chinese?

Reading and translating this book was a brand-new experience for me. It combines sound theology and spirituality. I enjoyed and benefited a lot from the process.

It will resonate with some Chinese. I say some, because many Christians are still used to light reading—short stories and testimonies. Some might think of it as too theological.

CP: Why do you think Chinese Christians are accustomed to light reading?

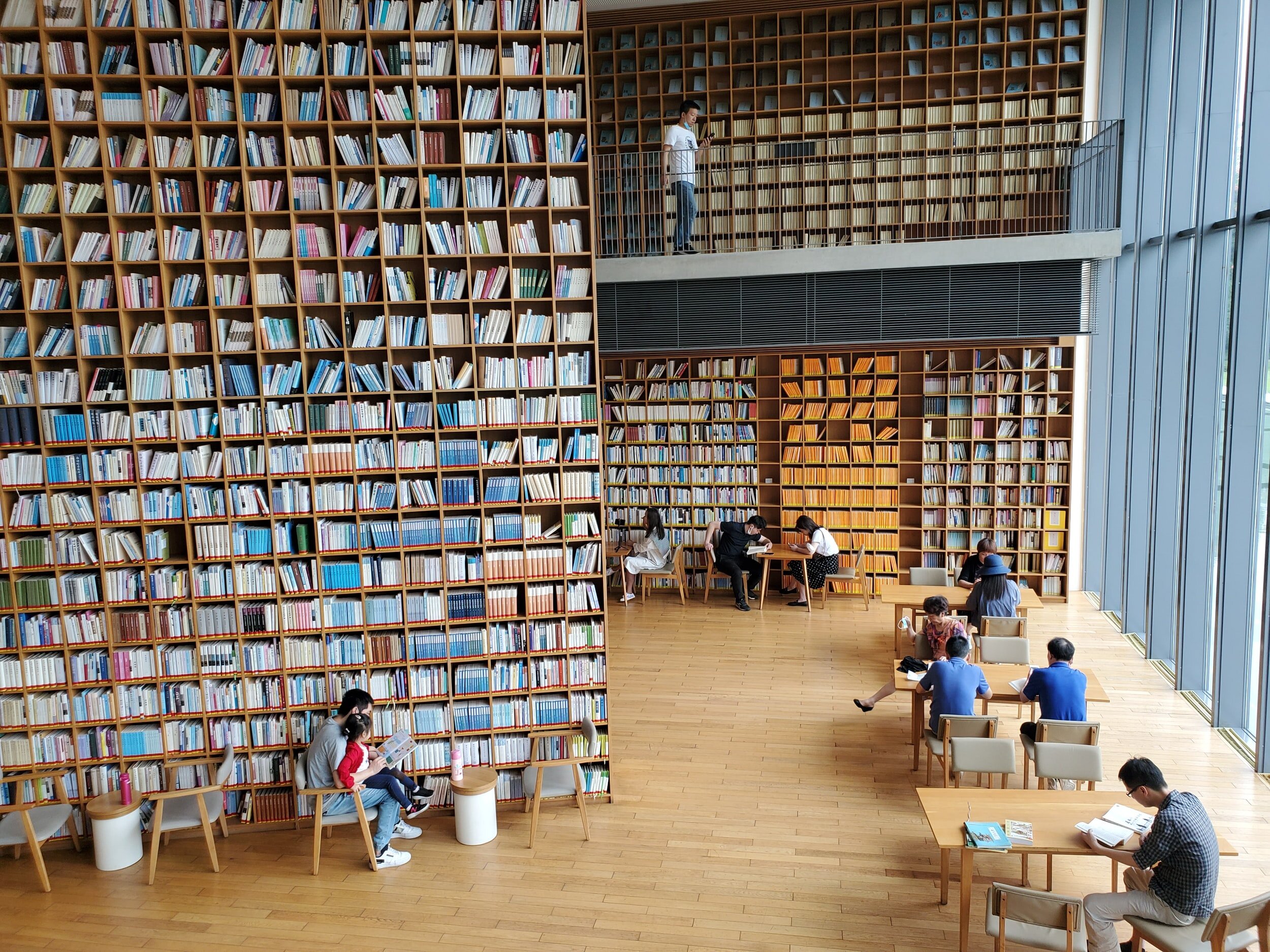

Well, I think it’s not just Christians, but Chinese people in general don’t read much anymore. Compared to the rest of the world, Chinese people read relatively little. So the average Christian, like the average Chinese person, likes to read less and less, and more and more people like to watch videos. How many people do you see in the subway in China reading newspapers and books? Aren’t they all looking at their phones?

It’s the same in the West, but in China, it seems to be worse.

CP: You mention that the combination of theology and spirituality impacted you. Is this melding unusual in your experience?

Generally speaking, theological works tend to be more obscure, while spiritual works are more superficial. There are few works that combine these two aspects well, so this was a relatively new experience for me.

CP: Why do you think Valley of Vision is important for the Chinese context? There are a lot of other things you could translate, I’m curious how you chose this book.

Valley of Vision can direct people to a theologically sound knowledge of God and his work, and that knowledge is the basis for right feelings and right doings. This devotional work is balanced in motivating people in these three categories: right thinking, right feeling, and right doing.

I did not initiate the project; a publisher talked to me. That is the usual way of all my translation projects. Publishers know I am conservative and Reformed in theology, so when they have such resources, they look for suitable scholars or pastors. I am grateful that God put some very good brothers and sisters in those publishing companies.

CP: You said, “knowledge is the basis for right feelings and right doings.” Why is knowledge-based spirituality important?

If you know the wrong God, then the more zealous you are, the more devout you are, the more dangerous you are. If you know the true God in the wrong way, then it is just as dangerous. Only if you know the true God in the right way, then truth, emotion, and behavior can promote and complement each other.

CP: What are some of the specific parts of Valley of Vision that you find applicable for Chinese Christians today?

First, this book is all-embracing. It covers diverse themes.

Second, its focus on trinity, redemption, repentance, etc., is very helpful for Chinese Christians. Many other devotionals are focused on needs and supplications.

Third, most pages of Valley of Vision begin with praise and adoration. That sets a good example for our prayer.

CP: Why is this modeling of praise and adoration important for Chinese Christians to see?

One pastor has suggested that the four elements of prayer can be recognized by the acronyms ACTS: adoration, confession, thanksgiving, and supplication.

Valley of Vision does a good job balancing these four areas, and the average believer tends to turn prayer into “listing a laundry list of needs.” Their attitude is to let God serve us, not for us to serve God. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of our relationship with God.

In addition, only when church leaders realize these deviations and are willing to guide brothers and sisters to truly know God in the pulpit and in practice can we achieve large-scale revival.

CP: What do Chinese Christians have in common with, say, a Puritan in 1600s America?

Lay people play a very important role in Chinese churches, similar to Puritanism in seventeenth century America.

Puritans sailed to America looking for religious freedom, and millions of Chinese Christians are seeking for the same freedom through the house church movement.

CP: What does the role of a lay person in the Chinese church look like? How is this similar to or different from the role of Puritan laypersons in the 1600s?

In the 1980s, after China’s Reform and Opening and the restoration of limited religious freedom, some dedicated Christians began to open their homes, preach the gospel, and establish house gatherings, thus giving rise to many small churches. These lay leaders actually do the work of pastor, elders, and deacons. Among them were many women preachers.

CP: What are some of the challenges to a translation project like this, from somewhat archaic English into modern-day Mandarin?

I needed to consult dictionaries and a U.S. pastor for the meaning of some archaic words.

The original lines are not in rhyme, and I aim at making it both instructive and artistic, like other Chinese poems.

CP: Stylistically, what is important to Chinese readers?

Chinese readers expect richness and literary content. They don’t expect a high level of literary quality, but at least a smooth reading. When many foreign works are translated into Chinese, the quality of the translation is so poor that it makes people angry to read them. Some translations are not even fluent. There are also good translations that are pleasing to the eye. I, as a translator, hope that my translations do not cause pain and suffering to the readers.

CP: What do you hope will be the impact of bringing this work to China?

I hope this work will first edify Chinese pastors and workers, then they can use this book to influence their congregations. I hope this book will help Chinese Christians know God better, love God more deeply, and follow God forever.

FOR PRAYER AND REFLECTION

Here are a few ways to pray for China, based on this interview:

-Pray for more Chinese authors to produce original pieces that can bless the Chinese and global church.

-Pray for God to bless the minds of translators who are laboring to bring rich, literary spiritual works to Chinese Christians.

-Pray that Chinese Christians will truly know the true God. Pray for them to follow him in their thoughts, their emotions, and their actions.

Our blog exists, not just to share information, but to resource the global church to share the joys and burdens of the Chinese church. Our hope is that everything you read here will lead you to intentional, knowledgeable prayer for the Chinese church.