Ryan moved to the United States from Guangzhou, China at the age of twelve, and has lived in three U.S. cities and two different continents since then. Ryan received his Master of Divinity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and is currently serving as a church planting resident at New City Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, OH, his US hometown. Before moving to Boston for seminary, Ryan lived in Washington D.C. for seven years, first as a student at Georgetown University and later working for a law firm. It was during his time in D.C. that Ryan met his wife, Abigail, who shares his love for history and classical music. In his free time, Ryan likes to watch Chinese dramas, cook, swim, and listen to Beethoven.

In the past few months, two of my friends, Hannah Nation and Jeff Kyle, have both reflected on how their lives have been shaped by China. Of course, unlike Hannah and Jeff, China is my birthplace and is still the country of my hometown. I was born in Guangzhou, China, in the mid-1980s and I lived there until immigrating to Ohio at the age of twelve. My relationship with China is certainly very different from those of my friends, and I want to join them in reflecting on how China has shaped me as a person. I hope it will help you understand some of the ways we look at our country and what China’s rise to be a global power has meant to many people of Chinese heritage. But before I share more specifically how I have been shaped by China, I want tell you a little about my parents and my childhood in China in the 1990s.

My relationship with China was primarily shaped by my parents’ relationship with the country. My parents were born in the mid-1950s. Unlike the American baby boomer generation, my parents lived through the famines of the Great Leap Forward, the social unrest and persecution of the Cultural Revolution, and the uncertain opening of Chinese society in the 1980s.

Just when everything began to look up, the Tiananmen Affair happened in 1989, when I was just two and a half years old. During my early childhood, China was still recuperating from the shock within and the international condemnation and isolation from without. We wanted the outside world to know that we could be peaceful, prosperous, modernized, and educated, all the while still holding on to our “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

This offered me an opportunity to witness some of the most transformative social changes in China in recent history. I was taught that modernization and science would lead to a prosperous society, education would place us in respectable jobs, and economic power would earn us respect. Meanwhile, the shame of living with Western imperialism was still fresh in our collective memory. In school, we learned about the “Eight-Nation Alliance” of colonial powers that invaded China during the Opium War and we heard stories about the Japanese occupation during WWII from our grandparents. Although we were eager to prove ourselves to the outside world, we also viewed the outside world with skepticism and distrust.

We lived in one of the biggest cities in China, but when I first started elementary school, we would meet in one-story huts whose roofs would leak during rainy days. We had not yet heard of McDonald’s or Pizza Hut, none of our homes were air-conditioned, and the best toys I had were the ones passed onto us by our relatives in Hong Kong. The first major change in my life occurred when my school moved into a brand-new, six-story building in 1994. Unfortunately, this was not the only major move that year. In the great transition from public enterprises to private companies in the early 1990s, many state-owned companies began to decline. Since our little apartment was provided by my parents’ work, the decline of their state-owned company also meant the loss of our home. This was not particular only to my family. Others like my parents – in their early 40s and poorly educated due to the Cultural Revolution – suddenly found themselves without work and without a state safety net to support them.

One small improvement did have a major impact on our lives. Because we lived only a little over one hundred miles from Hong Kong, Hong Kong television shows became available to us beginning in 1992, even though at the time, Hong Kong was still a British colony. Through these TV shows, we saw what a truly modern city looked like. We learned for the first time the names of many Western establishments and celebrities, and we saw news reports about America and Europe that were not always available on Chinese TV. And yet, watching Hong Kong television was another reminder that one of our best and most prosperous cities was still under foreign rule.

By the mid 1990s, the first McDonald’s arrived in my city. Pizza Hut and Kentucky Fried Chicken followed shortly after. We knew what they were because we had seen their commercials on Hong Kong television, but they were still too expensive for us. When my oldest cousin made enough money to treat us to a nice meal, she took all of my cousins and me to eat at Pizza Hut. I had two slices of pizza during the Chinese New Year of 1997 – that was perhaps the most memorable meal of my young childhood.

On July 1, 1997, almost everyone I knew stayed up until midnight to watch the handover ceremony in Hong Kong, during which Great Britain transferred the sovereignty of Hong Kong back to China. Hearing the Chinese national anthem being played in Hong Kong for the first time in over one hundred years put tears in all of our eyes. Two years later, a similar ceremony took place in the smaller city of Macau, as Portugal returned the sovereignty of Macau to China. Although these events had been in diplomatic negotiations and planning for over a decade, their arrival still signaled to many of us that China has risen again to reclaim the respect that it deserved.

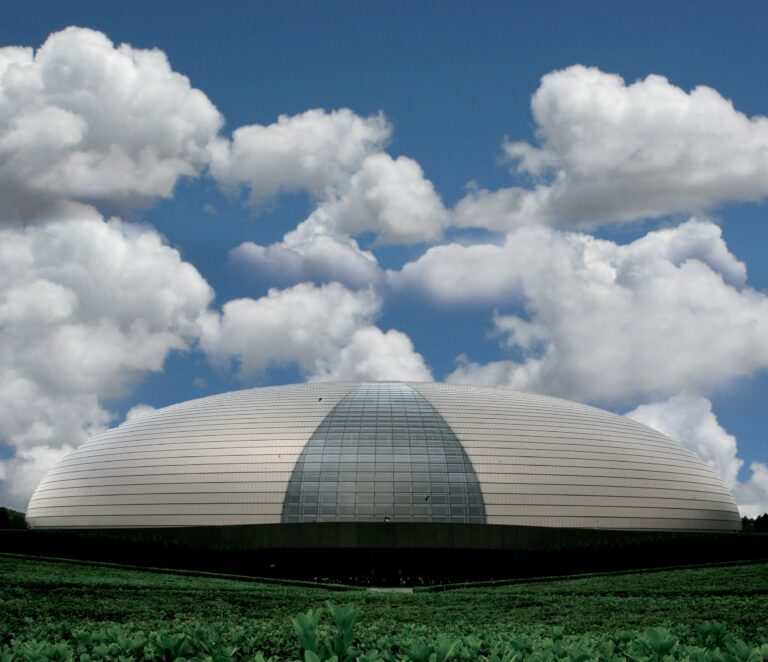

Very soon after the handover of Hong Kong and Macau, China was admitted into the World Trade Organization. In 2001, a little over two years after my family moved to America, Beijing was selected to be the host city for the 2008 summer Olympic games. Compared to the international isolation and disgrace after the Tiananmen Affair in 1989, the opportunity to host the summer Olympics signaled how far China had come in the 1990s, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Growing up during this period in Chinese history left some lasting impressions on my life.

Never miss a story

China taught me to remember our humble past. We have come through some hard times, both for China as a nation and for my family. We are only one century removed from colonial occupation and bitter civil wars. Memories of persecution and hunger during the 50s, 60s, and 70s still influence how my parents save money and prepare for the future. My parents have never expected life to be easy because everything they had was earned through sweat and blood. The curse of Genesis 3:17-19 was very real to us in the 1990s.

China taught me to be frugal. Frugality is a traditional Chinese virtue, but it took on a new significance for my parents’ generation. Because wars and social upheaval are still so fresh in our collective memory, many of my relatives live as if tragedies are no more than one generation away – preparing for danger even though we live in peace. When we first came to America, my parents stuffed our suitcases with plates and bowls and even a large chopping board. Even as we were heading to a land of opportunities, my parents still remembered the days when they had nothing at home and wanted to make sure this would not happen again.

China taught me to be fiercely loyal and grateful for the people around us. During the Cultural Revolution, when family members often turned against one another, and during many of the rough patches of the 1990s, my family relied on the good-will of our relatives and friends to keep a roof over our head. These experiences taught my parents to be grateful for the people around them. My mom used to tell me, “Repay a drop of kindness with a spring of water,” and I have seen my parents live out that virtue over and over again.

China inspired me with the power of collective unity. China’s rise in recent years was largely propelled by the collective energy and intellect of millions of people working together. A lot of people were amazed by the synchronized performance of thousands of artists in the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics, but for those of us who grew up wearing school uniforms and doing morning exercises in unison with our classmates, their performances were hardly surprising to us. From a young age, we have seen the wonders of discipline and collective power, and we are confident of our collective ability to meet new challenges.

We are eager to show the world what we have. From the 2008 Beijing Olympics, to the competitions in the sports arena, to the bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics, to even the most recent G20 meeting, China is eager to showcase its economic and cultural prowess as a signal that we are coming back strong as a civilization. Chinese people are proud of their meteoric rise in status, and they are not afraid to literally move mountains to achieve more success.