Sixteen years ago, my parents and I left China on an Air Canada flight for our new home in the United States. That trip was the beginning of my family’s long immigration journey to America. A lot has changed in China and in our family in sixteen years. Although my parents and I have returned to visit separately, we had never returned together. We finally got a chance to do so this past May, on the morning after my graduation from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. We reversed our steps from sixteen years ago, flying out of Boston into Hong Kong, and again on Air Canada. A few days into our trip to visit family and friends, my uncle asked me, “Do you feel your life in America is greatly affected by the rise of China?” I was not prepared for his question and gave a clumsy answer. But as I answered this question, it occurred to me that no matter what my answer, it could not douse the flicker of national pride behind his question.

As a young boy growing up in China, I too dreamed of being part of a powerful China. Even just a few weeks ago, when the U.S. women’s national soccer team took on the Chinese team in the World Cup, my heart was still hoping for a Chinese victory after having lived in the United States for sixteen years! Most Chinese students are well aware of the Opium Wars and their subsequent unfair treaties that forced China to relinquish sovereignty of Hong Kong and Macau to Great Britain and Portugal respectively. These national memories are still fresh in many people’s minds more than a hundred and fifty years later, and the country celebrated widely in the late 1990s as these sovereignties were returned to China. I could not imagine how someone like my uncle, who has lived through the Great Leap Forward, famine, Cultural Revolution, and Tiananmen Affairs, thirsts for national pride and respect.

The meteoric rise of China not only increased my uncle’s personal wealth, but also afforded him opportunities to travel the world. I used to travel to Europe thinking that none of my elementary school friends in China would have the experience that I was having. Now many of them are traveling to different continents for their honeymoons, while my wife and I drove to the Poconos. Yet as I see collective pride rising in many places in China, I also notice much insecurity and uncertainty. Like much of the Western world, which has been observing the rise of China with both wonder and suspicion, the people in China are also not sure what to do with themselves.

A fast-growing GDP cannot lift clouds of smog hanging above many Chinese cities. The increase in personal wealth can barely keep up with rising housing prices in large cities, leaving many young professionals or poor families stuck in rental homes. Families with infants and toddlers still fear buying baby formula that could be potentially harmful. After years of anti-corruption campaigns, average citizens still cannot rely on the government to speak up for them. And despite years of centralization in power, the national government is still too weak to govern a nation of 1.3 billion people.

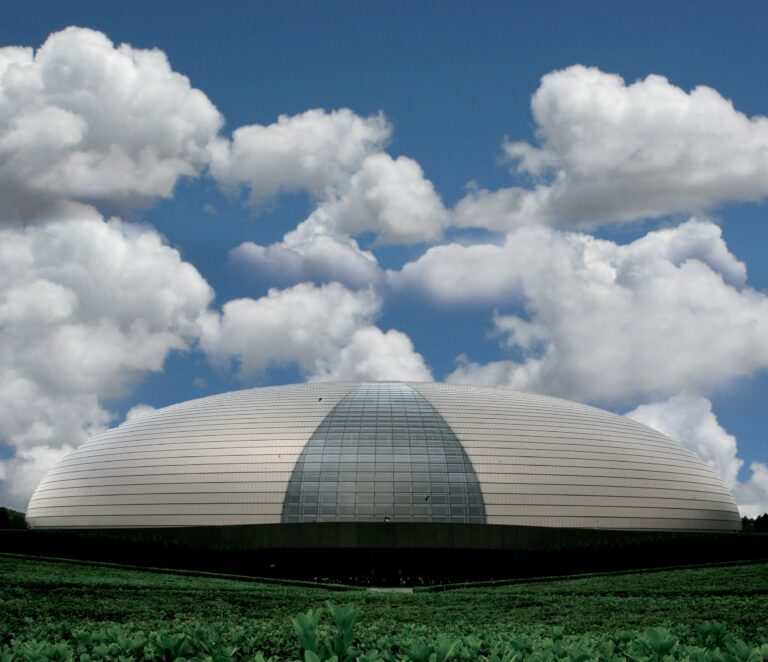

China is a nation with astonishing national projects – the Three Gorges Dam, a railway to Tibet, the Olympics, a World Expo, the Asian Games, and possibly another Olympics on the horizon – but behind this facade of national wealth, little shalom is found. The collective national pride does not translate into personal well-being. Even those who are wealthy live by overwhelming pragmatism. People are motivated to achieve, to win, and to gain at all costs, because they understand that even the most powerful dynasty has an end. The last dynasty in China only ended a little over a century ago, and it may only be a matter of time before this dynasty crumbles. The memories of famine and social unrest are still so fresh in the older generation’s mind that the present prosperity appears to be a temporary respite rather than a lasting peace. Therefore, everything happens in a rush: people rush onto buses, rush to take pictures of tourist sites, rush to buy, rush to sell. As one of my pastors would say, and this is especially true when it comes to China, “YOLO always begets FOMO.” The people are hungry for more, but they are waking up to the cruel reality that material wealth and national pride cannot bring them more.

Despite all the chaos and insecurity, there lies in China a people whom I love and a nation that I still hope to see flourish. There is cuisine admired worldwide, history that rivals fictional epics, and collective energy and ingenuity that resemble a kaleidoscope of God’s power and creativity. China is a country beaming with potential to become much more than what we see today. It is a nation hungry for respect and admiration; hungry for meaning.

As followers of Jesus who seek to relate to and love our Chinese neighbors, we must see reality – even conflicting realities. China is a country filled with contradictions, but also with confidence and pride. The people are hard-working, frugal, and creative. Most importantly, they bear the image of God. We do not have to see China as a competitor to be reckoned with. We cannot approach China thinking that we have some secret knowledge to pass along, or some democratic expertise that can improve its society. To reach China and to gain the trust of its people, we should learn to see its potential, to imagine what it could be, to promote shalom in its society. Perhaps we may even reach out to our Chinese friends and say, “We admire and are proud of what you have achieved, and we believe that under Christ’s lordship, China can be much more.”

Ryan currently lives in the Boston metro area and is a graduate of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. He immigrated to the United States from China in 1999.